Kentucky’s Beloved Ignorance: How We Banned A Book About Us

How a book about a story of grief, motherhood, and slavery in our state was banned by Kentucky parents, when a student like me learned a lot.

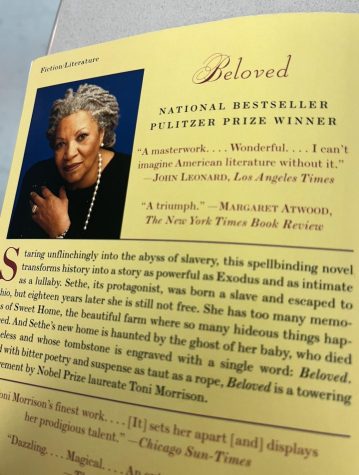

Beloved by Toni Morrison is very difficult to read, but I can’t help but think that is what makes it worth the while. Banned Books Week, from September 18-24th, and History of Kentucky with Dr. Sergent inspired me to read this book and while it was a tedious endeavor, to deprive another willing, learning student of the emotional understanding this book provides would prevent their desired growth.

Beloved, but Banned?

Beloved is banned supposedly because of what the Banned Book Project article on Beloved by Carnegie Mellon student Talia Buksbazen details: “‘In 2007, two Kentucky parents raised concern to the Eastern High School school board about violence within Beloved. Beloved was taken off the reading list for AP English Literature the following year, replaced with Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter” (Buksbazen). They aren’t wrong for saying Beloved is violent. The novel deals with heavy themes like sexual assault, death, trauma, etc. This book, however, is a deep, unfiltered glimpse into the horrors of slavery, thus, it would dilute the entire story to shy away from the truth. Specifically, Kentucky’s history with slavery is placed under Morrison’s lens and, ironically, is the homestate of the parents who complained. What some people might not know if they skipped Toni Morrison’s foreword, is that the reason it takes place in the Bluegrass state is because the story is heavily based on a real enslaved mother who was faced with an impossible choice in Covington, Kentucky, 1856 (approximately).

The Mothers of It All

Margaret Garner was an enslaved woman who attempted to escape Maplewood plantation in Boone County, Kentucky with her several children. Her plan involved traversing the frozen Ohio River into the free state of Ohio, but U.S Marshals and “slave-catchers” followed their trail. Upon reaching the escaped family, they discovered that Margaret had killed her daughter and attempted to kill her two sons in order to protect them from a return to slavery. Furthermore, as she was being taken into custody and her captors were turned away, she silently released her infant into the frozen river. She was tried for murder and sent back to a slave state, notably insisting that her deceased daughter had become a bird who had flown into freedom. Garner is also infamously quoted with her thoughts on her actions with: “I did the best a mother could do and I would’ve done better and more for the rest. I’ve done the best I could” (Garner).

This story of a tainted motherhood is not only a part of the our nation’s history, but is a story of Kentucky’s history with slavery. Toni Morrison found inspiration for Beloved in her recollection of a newspaper clipping she helped create in The Black Book summarizing Garner’s story. Her story intrigued Morrison, especially while the author dwelled on freedom and womanhood as the 80s progressed, stating: “ The historical Margaret Garner is fascinating, but, to a novelist, confining…So I would invent her thoughts, plumb them for a subtext that was historically true in essence, but not strictly factual in order to relate her history to contemporary issues about freedom, responsibility, and a woman’s place” (Morrison XVII). She later explains how she seemingly watched a ghostly woman step out of a lake near her house and Beloved is born.

The Story of Generation Grief

With the story of Beloved comes Sethe, the Margaret of this story. Like Margaret, she escapes from Sweet Home, a plantation in Kentucky, is pursued by marshals, and makes the difficult choice of killing her young daughter. She serves time in jail and eventually finds her way back to her free mother-in-law’s house, 124. The reader, however, is oblivious to the full story when it starts, for Morrison wanted the reader to feel kidnapped, thrown into the plot as often as stories of the enslaved involve no certainty or predictability. We start the story with Sethe free, but after all the trauma she experienced in her time enslaved, the question is raised: is she really free? This also goes for a former enslaved from Sweet Home who is free, Paul D, who visits 124 and ends up staying to build a life with Sethe and her surviving daughter, Denver. Denver is shown becoming an adult, struggling with the effects of her mother and Paul D’s trauma, something she never experienced herself. In addition to the living people in house 124, there is Grandma Baby, the way the refer to the ghost of the child Sethe killed and buried under a headstone that reads “Beloved”. This ghost’s presence is never questioned, as it appears so certainly and physically, with every visitor commenting on how stepping into the house is heavy and dark. This unconventional day-today becomes even more confusing when a young woman with dark, black eyes, a disoriented, yet sweet demeanor, too much knowledge of Sethe’s early life, and only answers to Beloved appears. She soon takes the house under her control, somehow not immediately alerting the members with her clear connection to the deceased child.

The story twists and turns between perspectives of characters, periods in time, with long blocks of descriptive text on each page. As Beloved grows to be more of an angered, dangerous presence, and each character goes through their own arch, the reader has no choice but to faced with the encompassing effect of slavery on this household. The question that is raised is almost undoubtedly answered: no, even though they are technically free, they are never truly free.

A Student’s Review

My overall review of this book is that, as aforementioned, it is heavy. It is long, dense paragraphs of texts that depict really tragic, upsetting stories. This, however, is exactly why it is worth the read. I think to ban a book like this is to choose ignorance. In my opinion, one cannot learn about slavery without facing the true reality and thus, horror that it was.

Specifically, Kentucky isn’t usually considered part of the Deep South, so I have found that our past with slavery has been described as “mild” or just not talked about enough. Is there really such a thing as mild slavery though? After reading this book, I can confidently say no. Not to mention, details on the effect of trauma on people is something I feel that our society is trying to and should learn more about. I don’t feel that it is fair that true crime fanatics can obsess over the twisted minds of serial killers, students are forced to watch gruesome 9/11 documentaries every year, we push for more recognition of mental health as a serious alignment, but we deny the decades of trauma in Black individuals at the result of slavery. Additionally, one must think about Sethe and Denver’s story, a mother who is an escapee of enslavement and a daughter who was raised free from it. Denver still is left with the trauma of her hurting mother and her deceased sister, which Denver could easily pass on to her child and so on. It is a story of motherhood and the great sacrifice made, but the emotional mess that comes from that. This book does an excellent job of not filtering anything, using Morrison’s poetic language and thought-provoking statements to allow the reader to not just understand, but feel what each character is feeling as much as possible.

Did I have to take breaks? Yes. Would I read this to an elementary school child? No. However, if there is a mature student willing to see the truth about this undeniable part of our history as a nation and as a state, should they be able to read it? Absolutely.

I did the best that a mother could do, and I would’ve done better and more for the rest. I’ve done the best I could.

— Margaret Garner

Rylie Sudduth is a senior at WCHS and so excited for her first year with the Jacket Journal!! Rylie’s passions outside of school lie with the arts, so...