An exposé on the groundbreaking work WCHS ag students and disability advocates have been doing.

Our presentation and design ended up winning, which awarded the WCHS agriculture program $30,000.

Over the past seven months, WCHS students involved with Mr. Richardson’s agriculture classes have teamed up with disability advocates in the school, trying to create a universal work cell for a factory in Lexington called Parker Hannifin. Parker is a global manufacturer of o-rings, which helps seal air inside of everyday things like cans, to things as specialized as scuba gear, jets, rockets, and more.

Parker is looking to make their facilities more accessible for all so that people from all walks of life will be able to have the same opportunities. We were just one of sixteen groups contacted about this opportunity to make the workplace an equal setting. One of the others is Berea Makerspace, a staple for the creative minds in Berea. They were the only other ones who accepted the challenge. Both groups presented our final designs for the project on April 26th at EKU.

Below is a gallery that details the process of the project, what it will do, and the outcome.

Main team leads Hunter Davis (11) and Weslee Sturgill (11) showcase Woodford County’s work cell design.

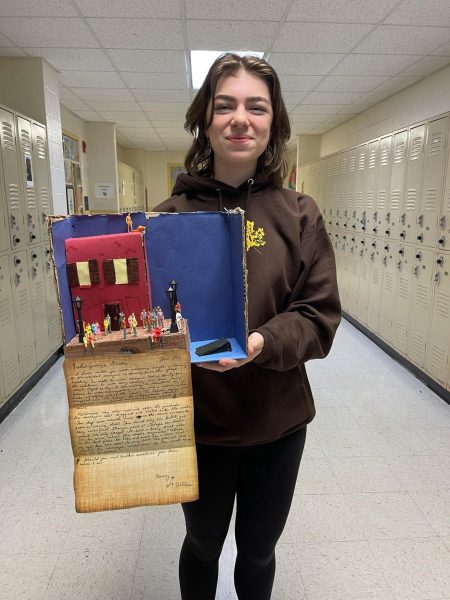

Gabby Villareal (11) was involved along with me, as a disability advocate. Not pictured is Andres Fajardo (12), a fellow disability advocate along with us.

Morgan Browning-Gibson (12) was one of the team leads in Mr. Richardson’s class. Who wasn’t pictured was James Luthi and Ryan Sechrest, fellow team leads.

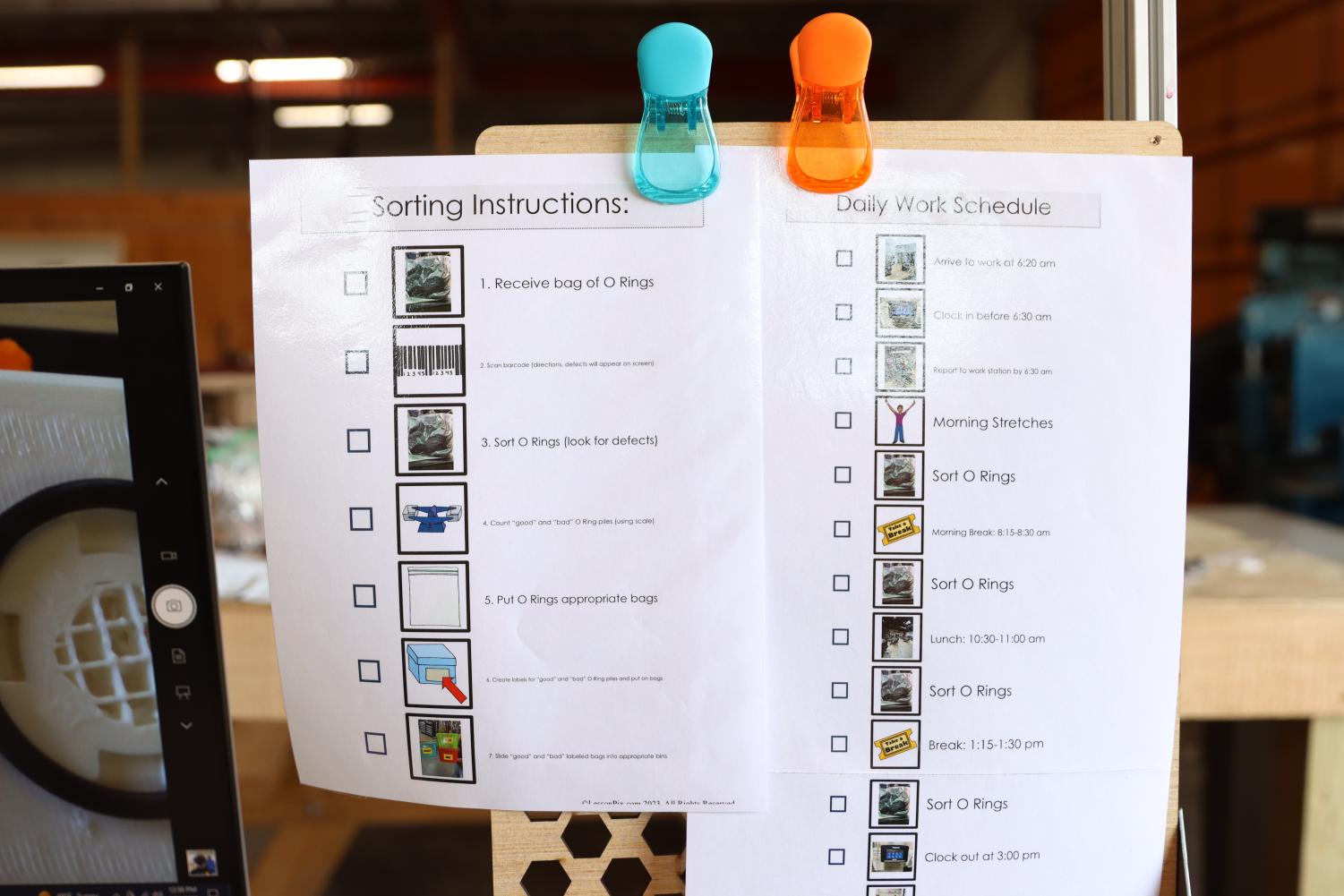

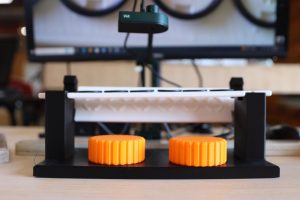

I’ll now be going over the design, from top to bottom. At the top. there’s a daily work schedule for people who need visual cues or like routines.

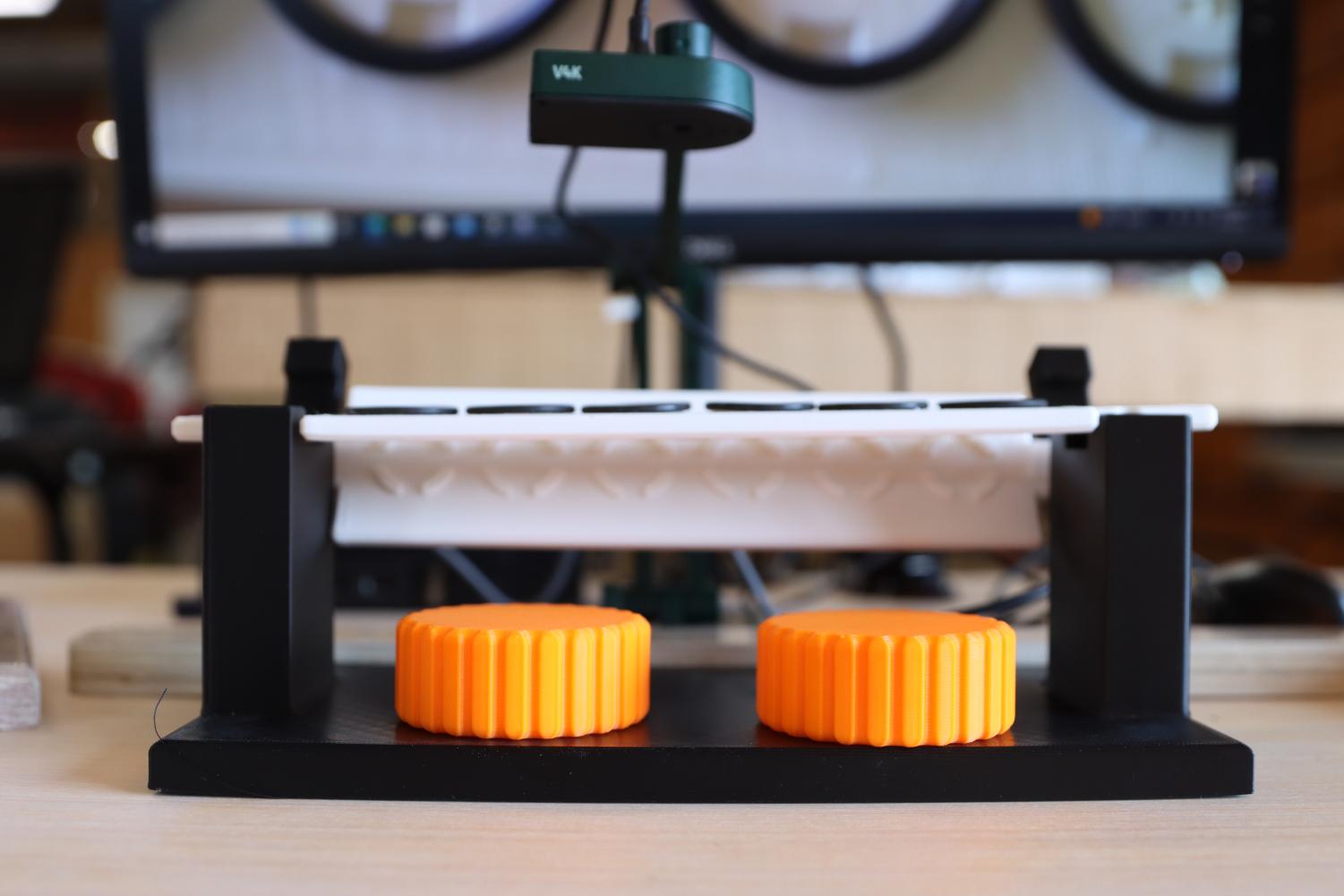

These work cells are outfitted with a camera, a monitor, and a keyboard. This assists visually impaired people in inspecting o-rings, and just makes it more convenient overall.

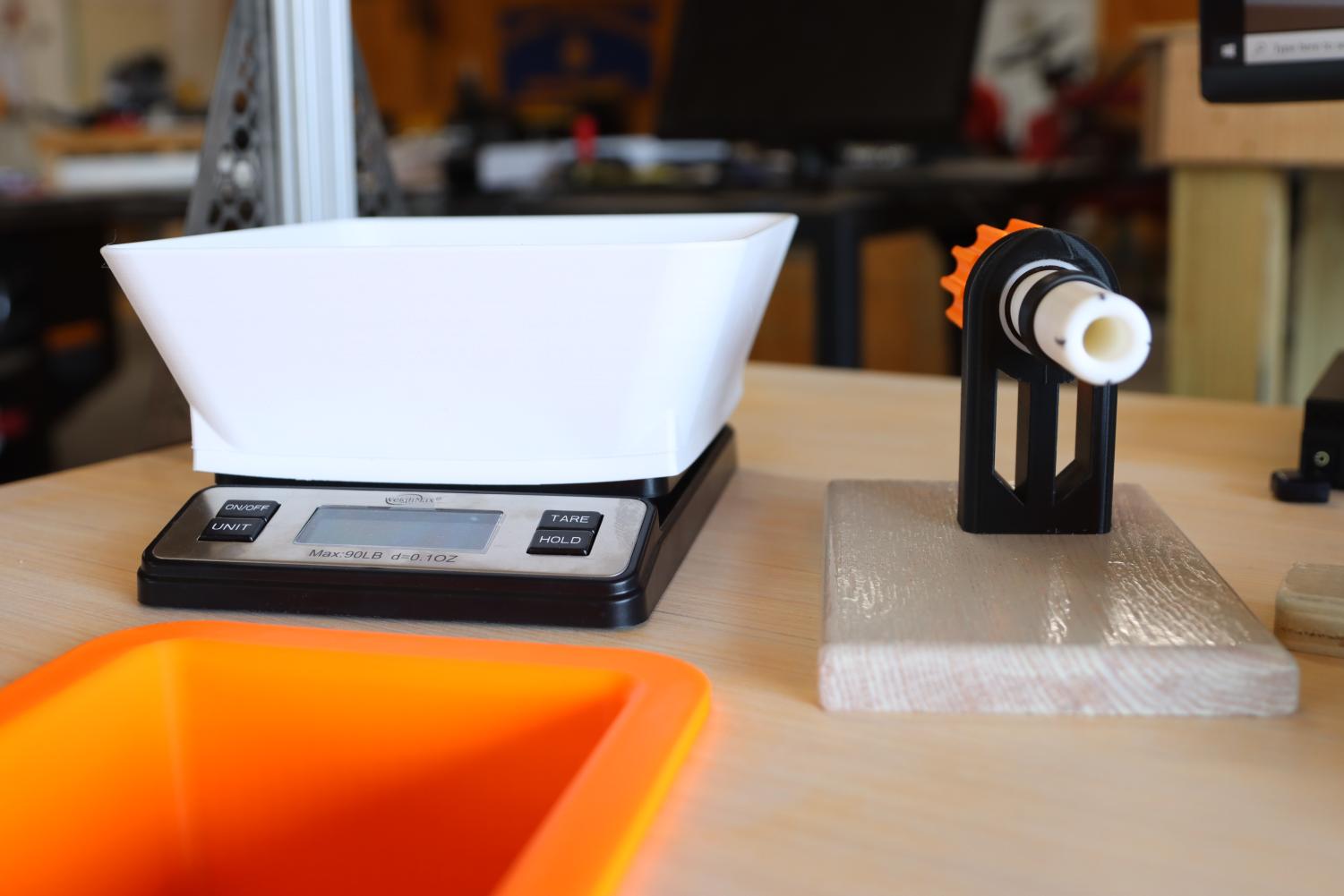

People would inspect the o-rings in groups of six, using a device aptly named “The Flipper”, which is the device with the orange knobs.

Workers would also use another device, that I call “The Twister”, as it rotates the ring to show imperfections on the top and bottom, by rotating the ring clockwise and counterclockwise.

After inspection, the rings are placed in one of two bins. Bad o-rings go in the red bin, while good o-rings go in the green bin. These bins are outfitted with X and thumbs-up symbols. These are present to assist colorblind people.

This is me working at the station. What isn’t pictured is what a worker would do after placing the o-rings into the bins. The bins have a ramp, and can be removed so the o-rings go down that ramp and into good or bad bags for final packaging or repurposing.

Our presentation and design ended up winning, which awarded the WCHS agriculture program $30,000.

To conclude, this experience has been very rewarding and eye-opening for me. I’m stoked to see what the future holds for universal designing, and in that same vein, what the future holds for people with disabilities in the workplace. Thanks for reading.