Where the Wild Things Came From

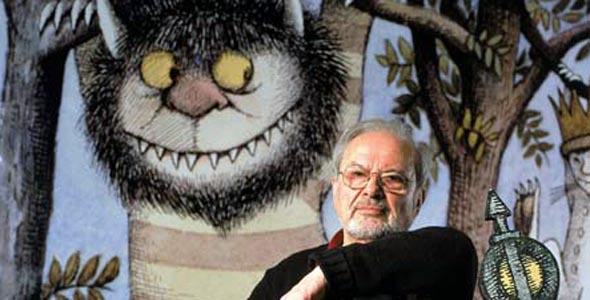

The Children’s Literature of Maurice Sendak

Maurice Sendak was an American illustrator and author of children’s books, best known for his Caldecott-winning Where the Wild Things Are (1963). With over forty titles and some of the highest awards given in children’s literature, Sendak has been called “the most important children’s book artist of the 20th century,” (New York Times). His works center on courageously imaginative young protagonists, and how they make sense of the messy and beautiful oddity that is life. When asked about his writing style, Sendak professed, “I only have one subject. The question I am obsessed with is: how do children survive?” We will explore three of his books in pursuit of an answer, representing some of his best-known and best-loved stories.

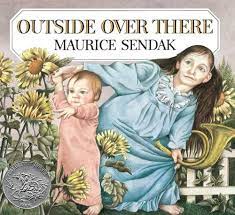

Outside Over There (1981)

Winner of the National Book Award and a Caldecott Honor, Outside Over There follows the journey of Ida, a girl searching for her baby sister and the goblins who kidnapped her. Left to watch her sister while her father is awat at sea, Ida is horrified when the faceless, robed creatures sneak into the safety of her home and leave a sinister ice baby in place of the child. Armed with nothing but her mother’s rain cloak and her favorite horn, Ida leaves her picturesque country house and ventures into what Sendak calls “outside over there.” The illustrations, more painting-like than other Sendak works, are massive in scope and soothing in tone, portraying an idyllic German-Romantic landscape perpetually graced by the sea, a reminder that Ida’s father is gone and she must deal with the situation on her own. Ida “survives,” by her own internal strength and cool head, overcoming fears of a wide and unfamiliar world and returning home with horn and sister in hand.

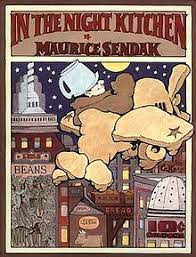

In the Night Kitchen (1970)

Another Caldecott Honor, In the Night Kitchen features the loosest plot of the three. Mickey is a young boy who floats out of his bed and into the “Night Kitchen,” a brightly lit cityscape of giant food cans, milk cartons, and bread boxes. He lands in a bowl of batter, and is nearly baked into a cake by the kitchen’s three bakers. Mickey flies out in a plane made of cake mix and helps retrieve milk for the bowl. Like waking from a dream, Mickey sinks back down into his bed, always with a satisfied grin on his face. One could say he “survives,” by his constant wonder at the world around him, and his willingness to help not only complete strangers but strangers who have almost entombed him in pastry. Sendak often spoke of his love for comic strips as a child, and the pictures in this book evoke that defined, rough-around-the-edges style of illustration. These, along with a catchy rhyme scheme, have made Night Kitchen a favorite for story time repeats.

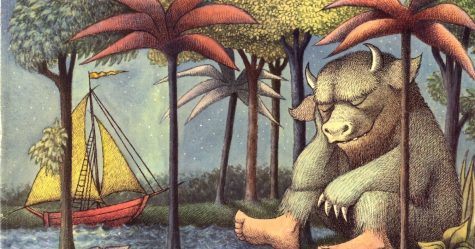

Where the Wild Things Are (1963)

One of the cornerstone childhood fears is that of abandonment. In Maurice Sendak’s magnum opus Where the Wild Things Are, troublemaker Max is not only sent to his room but sent “without eating anything,” a double-desertion that leaves Max with only his imagination for company. In his mind’s eye, Max sails to “where the wild things are” and meets its titular residents. After gaining their trust, he leads them on a “wild rumpus” throughout the land, howling alongside them with relish. Max “survives” not only by taking refuge in his creativity, but also in recognizing his ties to home and the real world. He returns to his room to find a hot meal waiting for him, a sign that he was never really alone. Winner of the 1963 Caldecott medal, Wild Things has remained a beloved storybook staple.

Joseph is a WCHS Senior, and returning editor and staff reporter for The Jacket Journal. An avid cellist, he participates in Woodford's Chamber Orchestra...