A Spooky Night of Shostakovich, Baber, Adams, and Saygun

An overview of the UK Symphony’s Halloween Concert.

The UK Symphony Orchestra season continued Friday night, with doctorate students Merih Erdem Özden and Sean Radermacher joining Maestro John Nardolillo in a thrilling Halloween concert. Shostakovich’s 5th Symphony headlined the program, along with UK composer-in-residence Joseph Baber’s Suite from Frankenstein. Contemporary works by John Adams and Ahmed Adnan Saygun will also be heard.

Want to discover these pieces for yourself? Click the hyperlinks and read along!

Dmitri Shostakovich (1906-1975)

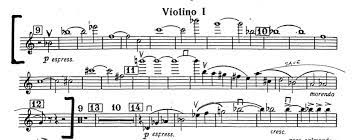

Symphony No. 5 in D Minor, Op. 47

the early 1940’s.

It was the summer of 1937, and Shostakovitch was writing for his life. The Communist party of the USSR had made “artistic purity” a priority among Soviet composers, and progressive musicians everywhere were facing arrest, deportation, even death. An editorial in Pravda, the infamous propaganda magazine of the party, called Shostakovich’s opera Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk a “formalist cacophony….muddle instead of music.” The premiere of his Fourth Symphony in C Minor had to be canceled on the threat of “administrative measures.” Having gone from Soviet poster-boy to denounced radical in a matter of days, the young composer had to force his work into a style that, put bluntly, would not send him to the Gulag. The resulting masterpiece has become an enigma for music historians and conductors, as it is unclear which elements of the work are meant to be taken seriously.

The first movement, for example, begins in a declarative set of minor sixths. However, this dramatic first theme only lasts four bars before coming to a three-note halt, softening into a mournful second theme. This three-note “dead end” will appear throughout the first movement, dragging the music down from the climax of a phrase in order to begin again. What could this mean? In a traditional symphony, the first movement is a kind of first impression, the most substantial and declamatory of the work. Here Shostakovich seems restrained, as his passages continually rise up and assert themselves, only to be cut short.

He continues the Symphony not with the typical slow movement but instead with a playful scherzo, another break from tradition. This homage to Gustav Mahler portrays a peasant dance floor, with stomping cellos, rustic clarinets, and wispy flutes alike taking their turns on center stage. After the prancing rabble clears the way, we finally get our slow movement. Widely considered to be a requiem for victims of Stalin’s purges, Shostakovich evokes rites from Russian Orthodoxy in its orchestration. He rations the lyrical passages among each of the string sections to convey the sound of a choir, with isolated timpani strokes completing the funerary scene. A haunting harp and celesta duo brings the movement to a close, with hushed strings delivering a “final benediction.”

The finale begins in a series of “upbeat, swaggering tunes” and triumphant military marches. An unexpected slow march connects the main passages with the coda, bringing back for a moment the sorrow of the third movement. The concluding measures are almost hard to listen to, as the concluding trumpet calls clash with high B flats in the strings before a final, minor cadence.

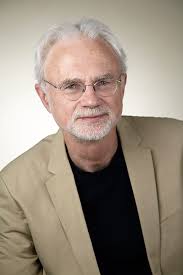

Joseph Baber (1937-)

Frankenstein Suite, Op. 40b

A performance of UK composer-in-residence Joseph Baber’s “Frankenstein Suite” commemorated the composer’s retirement after a celebrated career at the UK School of Music. The piece, described as “tonal with modernist outbursts,” is taken from Baber’s opera of the same name. Though the production itself is now deemed “unproducible,” its music has become popular among Halloween programs.

The first movement (Gypsy Dance) is a bombastic romp through jittery violin runs and blaring offbeats in the brass. The second (Bring Out the Dead), played by the strings, is slow and elegiac in contrast. A sequence of dissonant chords opens the third movement (Procession of the Judges), followed by descending figures in the strings and marimba. More a march than a procession, the presence of drum and triangle strokes gives the movement a militaristic feel. The fourth movement, the prelude to the opera’s fourth act, is a somber interlude, beginning and ending with a melancholic clarinet solo. The finale (Raising of the Monster) begins as a sinister tremolo in the lower strings, with accompanying flutes and violin harmonics. A drawn-out crescendo proceeds to the end, with interrupting brass and teetering percussion. The piece reaches a suspended dissonance of high-register shrieking, almost shouting “It’s alive!” as a rapid drumroll concludes the suite.

John Adams (1947-)

Short Ride in a Fast Machine

“You know how it is when someone asks you to ride in a terrific sports car, and then you wish you hadn’t?”

So wrote American composer John Adams on this “Fanfare for Orchestra” that has since become one of his best known works. Indeed, the almost manic energy maintained by repeated minimalist figures gives a sense of breathlessness, as if we are charging forward towards an elusive destination. “Short Ride” is a four-part cascade of contrasting off-beat lines, kept in time by woodblock strokes. Urgency pervades the piece, as more and more instruments add different rhythms to the mix, only to disappear when the tension seems highest. This particular use of polyrhythms, known as “rhythmic dissonance,” is an Adams staple. The pitches follow a similar pattern, with added tones gradually building up complex harmonic structures before de-crescendoing into a new tonality. These subito piano (suddenly quiet) “gate” bars mask the tonal shift taking place, but it doesn’t stay quiet for long. After amassing the full rhythmic and harmonic force of the ensemble for a fourth time, Adams gives the brass a concluding lick to a short drum beat. The final chord rings and the joyride is over.

Ahmed Adnan Saygun (1907-1991)

Ayin Raksi (Ritual Dance) Op. 57

Turkish composer Ahmed Adnan Saygun’s mysterious “Ayin Raksi” gives an eerie atmosphere appropriate for Halloween night. The piece begins in a trance, as a hushed, dissonant violin line floats among accompanying figures in the winds and harp. A solo flute tip-toes on high, before being taken over by a clarinet. A series of swooping gestures in the winds, strings, and solo violin jar the initial quiet, making way for a teetering section of arpeggios in the violins, violas, and bassoon. Things quiet down for a time, though the texture is cut into by uneven cymbal claps. Throughout the work, the music takes a discordant rise in dynamic, typically with an unsettling tune in the brass or winds, and then decrescendos into a calmer mood. At one point, the music is almost completely silent save for a low drone by a bassoon and an off-putting, march-like beat in the percussion. A familiar, sinister run in the high strings pierces through, only this time with the added shock of the brass. A drawn-out, almost unintelligible crescendo proceeds from there, with sliding figures in the flutes and strings glistening against prolonged, dissonant chords. The piece ends abruptly on the last of these chords, almost in bewilderment at where the last ten minutes have brought us.

Joseph is a WCHS Senior, and returning editor and staff reporter for The Jacket Journal. An avid cellist, he participates in Woodford's Chamber Orchestra...