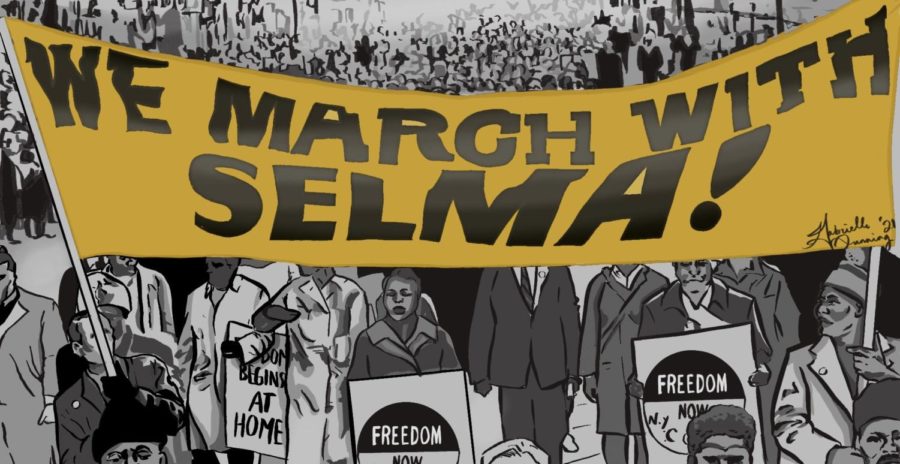

Digital drawing of the Selma March by Gabrielle Dunning.

The Days Leading up to the March from Montgomery to Selma

Bloody Sunday and Turnaround Tuesday

On March 7th, 1965, approximately 600 people stood behind the SNCC’s John Lewis and SCLC’s Hosea Williams and crossed the Edmund Pettus Bridge to attempt to begin the march from Selma to Montgomery. Troopers violently attacked the peaceful demonstrators in an attempt to stop the march for suffrage.

They had planned to march to the state capitol in Montgomery, 54 miles away, to protest the murder of Jimmy Lee Jackson by police in Marion, Alabama, during a protest and the lack of Civil Rights. Prior to the attack, The Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) had decided to not participate in the demonstration, it felt that marches gained too little while spilling too much blood – though it was decided that those in SNCC who wished to participate could do so on a personal basis.

On the bridge that Sunday, gas-masked state troopers and Dallas County Sherriff, Jim Clark, stood waiting to confront marchers as they started to cross and order them to halt. They knelt instead. In response, the officers fired tear gas as they charged into the group of kneeling protesters, swinging billy clubs and beating marchers; many marchers fled the best they could.

A federal judge issued an injunction, preventing any more marches until a court hearing could happen, so Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and the SCLC were apprehensive about violating a court order – they feared risking federal support for national voting rights. Instead, they led flanks of marchers to the Edmund Pettus Bridge the following Tuesday, knelt in prayer, and turned around. Young, radical protestors were outraged at Rev. Dr. King’s decision on “Turnaround Tuesday” and made plans to march on the capitol the next day.

On Wednesday, approximately 700 Tuskegee students caravanned to Montgomery to deliver their freedom petition to Alabama’s governor, George Wallace, but the police had different plans again. On Dexter Avenue, state troopers blocked the march, swinging billy clubs prompting the students to sit in the streets and sing freedom songs. Gov. George Wallace refused to meet with them, and when Tuskegee’s George Ware attempted to read the petition, he was arrested. As the day continued, the state troopers wouldn’t allow the protesters to leave, even to the restroom. Prompting Jim Forman to “just do it here” earning the protest the name “The Great Pee-in” and after midnight, heavy, cold rain forced the protesters to seek shelter in the nearby Dexter Avenue Baptist Church. The next morning, SCLC’s Jim Bevel showed up to dissuade them from continuing the protests because they were drawing attention from the Selma campaign and as SNCC members angrily left the church to resume their demonstration, state troopers arrested them and beat others inside.

The following Monday, SNCC members resumed demonstrations with approximately four hundred Alabama State University students, but police once again surrounded and beat demonstrators and, unprovoked, Black residents in the district. At the march the next afternoon, television cameras recorded the officers attacking the protesters with whips and lariats.

Forman’s rage came out later that evening at an SCLC-sponsored rally in a Montgomery church. He declared from the pulpit, that President Lyndon Johnson was the only man with the power to stop George Wallace and the Police. “I said it today, and I will say it again, if we can’t sit at the table of democracy, we’ll knock its f***ing legs off!” – At this point, Forman and many SNCC staffers no longer put their hope in the Federal Government. When the march from Selma to Montgomery finally happened, “some SNCC people served as marshals,” Forman explained, “but we had generally washed our hands of the affair.”